26 Nov Collective Spaces: How Public Plazas Promote Community Engagement and Well-being

This is a guest contribution by Ronika Postaria

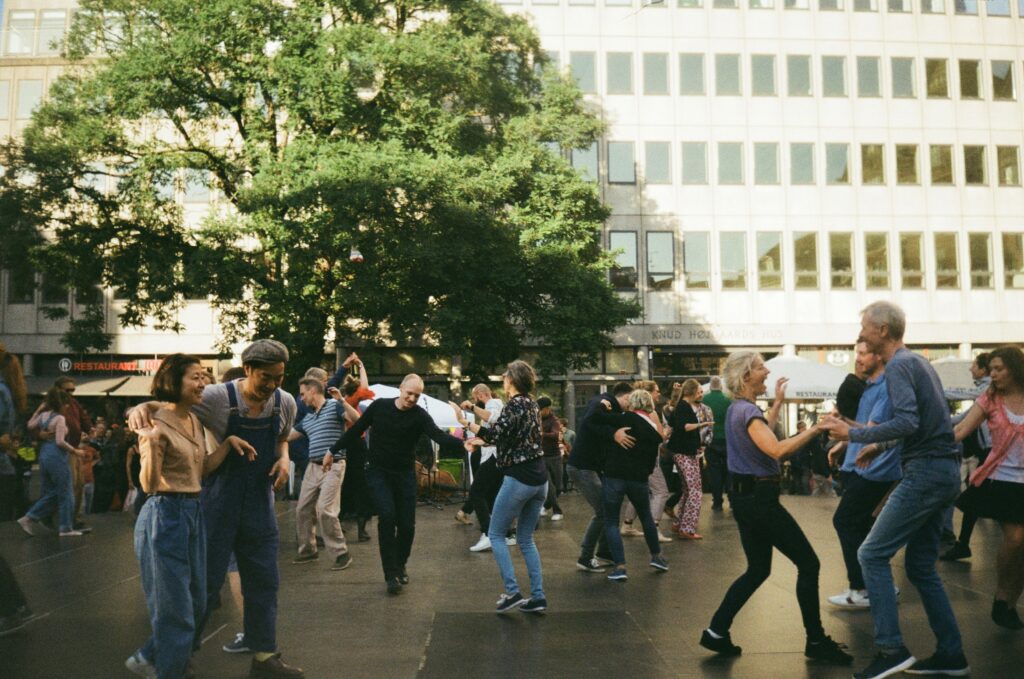

Image credits: Unsplash.

Public plazas are integral, shared social infrastructure. However, in Toronto, several public spaces have either restricted access, inadequate weather protection, or limited design features, making them unpleasant and unsuitable for the diverse needs of the community. This often makes them feel uninviting or exclusionary to marginalized groups, reducing their effectiveness in promoting urban inclusivity.

Places that are overly planned or lack inclusive design aspects tend to serve specific demographics, leaving sexuality, race, ethnicity, religion, cultural background, and socioeconomic status out of the equation. Hence, poorly designed public areas amplify urban social isolation rather than alleviating it.

The Social Impact of Exclusionary Public Plazas

Social isolation is a pressing issue in Canada. A 2022 survey revealed that around 18.3% of Canadians aged 15 and older experience mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders, indicating significant mental health challenges.

What can we do? Thoughtfully designed public spaces can foster social engagement, promote psychological resilience, and influence how we interact with and contribute to our community. Commercialized or strictly regulated public spaces favour certain users, thereby negatively impacting the sense of belonging and accessibility for various demographics. In Canada, Black, Indigenous, and people of colour are more than twice as likely to face harassment or discrimination in parks compared to white individuals. This exclusion makes public plazas unfriendly, rather than inclusive community hubs.

Addressing Social Isolation and Mental Well-being

The effectiveness of any public plaza depends on its ability to meet users’ needs and reflect their identities. Participatory design with community members is crucial for creating inclusive and inviting spaces. However, it is equally necessary to bring diversity to our public spaces—not just cultural diversity but also broader user groups.

Below are a few design motivations that allow public spaces to better serve the community:

1. Opportunities for Informal Socialization

Casual, unplanned social interactions in public spaces can address loneliness and depression to some level. Well-designed public plazas can become “third places”- spaces beyond home and work, where informal interactions can flourish. The goal is to encourage people to linger, engage in conversation, and share experiences in public spaces, rather than passing by quickly.

A notable example is Bryant Park in New York City. Adding movable chairs, small café kiosks, free events, and casual lawn games transformed the park from an underused space into a vibrant, socially engaging hub, boosting perceptions of safety and community cohesion. Another interesting factor is that the park offers something for everyone, from yoga sessions and outdoor movie screenings to concerts and even free book rentals. This encourages community get-togethers and frequent visitation. Further, regular activities not only keep plazas lively but also help prevent underuse.

Facilitating unplanned, informal community gatherings in public spaces is one of the easiest ways to boost a sense of belonging and community life, and to bring joy to the otherwise fast-paced, yet mundane, city life. For a city like Toronto, with its residents identified among Canada’s loneliest people and 43% of adults never seeing their neighbours, there is a need to optimize the public realm at all times. Local governments should promote and incentivize flexible, modular designs for public spaces that can evolve with the community’s needs. Programs such as farmers’ markets, street performances, and pop-up events can also enhance informal social opportunities without requiring significant infrastructural investment.

2. Multigenerational Features:

Most public places are designed with specific user groups in mind – mostly, these are children and young adults, with some thought to gender and safety. But for plazas to be truly vibrant and inclusive, they must cater to people of all ages.

Children and their caregivers thrive in interactive play spaces with stroller-friendly pathways, while teens and young adults seek informal spots for socializing beyond traditional commercial settings. And for older adults, this means providing accessible seating, shaded areas, and safe pathways. The key is to bring all these features into a single space, including design features that serve individuals with disabilities. For instance, smooth surfaces, ramps, varied-height seating, and adaptive furniture that can be rearranged are likely to cater to different groups throughout the day, rather than being active for only a few hours.

Maggie Daley Park in Chicago, USA, is one such park that features layered activity zones within a single contiguous area, each tailored to different demographics while maintaining visual and spatial connections. A children’s play garden strategically placed near areas that cluster caregivers and seniors to observe and socialize while children play. Accessible walkways, such as the Looped Ice Ribbon, accommodate various mobility devices, including wheelchairs and strollers. This thoughtful design ensures safe movement for seniors and people with disabilities throughout the park. On the other hand, active features such as rock-climbing walls and ice-skating rinks keep teens and adults excited. This mix of activities allows families and individuals of all ages to enjoy active and leisure time together. Additionally, visual connectivity is enhanced by low planting and transparent railings, which maintain sightlines between zones, creating a sense of shared space. This successful integration of various activity zones fosters an inclusive environment for the community.

By 2036, over 25% of Canadians will be 55 or older, making it vital for designers to prioritize aging in place. Perceived environmental barriers outside are directly linked to physical inactivity and a reduction in participation in community events. Drawing on the previously discussed ‘informal socialization’, Canadian cities need to integrate amenities, housing, and social engagement: accessible public spaces within walking distance, safe pedestrian crossings, wide and well-maintained pavements, clear signage, ample shaded seating, and community hubs dedicated to seniors. Furthermore, inclusive events, such as walking clubs, fitness classes, or cultural gatherings, that enhance older adults’ participation in the community are also essential for the overall quality of life.

3. Cultural Sensitivity:

Canadian cities are inherently diverse, yet public spaces often fail to reflect this diversity. With one in four Canadians being immigrants, representation in urban design is vital to fostering a sense of belonging, safety, and identity.

Place des Festivals in Montreal is renowned for its year-round, multi-seasonal, and culturally inclusive design, featuring ample seating, interactive water elements, and cultural programming that attracts over 40 festivals annually, engaging both residents and visitors.

Plazas have the space and potential to weave and reflect the community’s cultural diversity through public art, multilingual signage, and programming that celebrates various traditions. More cities need to start integrating Indigenous placemaking principles, showcase the histories and languages of immigrant communities, and create environments where everyone feels welcome and represented. Whether through murals or flexible spaces for storytelling and cultural celebrations, the potential to enrich our urban environments is immense.

4. Mental Health-Centric Design:

Public spaces need to move beyond superficial improvements and adopt design approaches rooted in psychological, sensory, and social science. Research indicates that well-designed public spaces can positively impact mental health by fostering socialization, promoting physical activity, and providing access to nature. Greenery, natural shade, noise buffers, water elements, and art not only transform ordinary plazas into tranquil oases but also benefit neurodivergent individuals who thrive in sensory-friendly environments.

Green space in Toronto is limited and unevenly distributed throughout the city. As a result, all citizens, especially marginalized communities, are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of nature deprivation and urban overstimulation, underscoring the need for greater attention to addressing inequities in access to high-quality public spaces.

The Bentway Conservancy in Toronto demonstrates how thoughtfully designed, nature-rich public spaces can significantly improve mental health by reducing loneliness and stress. Their 2024 Rx for Social Connection study found that 62% of visitors reported better mental health after their visit, and 64% felt more socially connected. The Bentway integrates natural elements, flexible seating, and public art to create inviting spaces that encourage interaction.

Another successful case is Seoul’s restoration of the Cheonggyecheon Stream, which demonstrates the psychological benefits of re-naturalizing urban waterways. The project removed the elevated freeway and the concrete deck covering the stream, which were obstructive, and replaced them with permeable surfaces that ensured continuous water flow through pumping systems. Following the restoration, the corridor now attracts 64,000 daily users from all walks of life.

Rethinking Public Plazas as Collective Spaces

Future urban planning must prioritize the development of plazas that celebrate diversity, encourage interaction, and promote community well-being. Public Spaces should be communal hubs that promote social interaction and foster community cohesion. They can bring people together and promote fairness in urban areas when designed and managed using participatory approaches, evidence-based design, and policy-driven solutions that consider inclusivity.

Fostering social connections has multifold benefits, from upstreaming health resources to reversing trends of isolation. Moreover, the economic ramifications of inaccessible public spaces or break areas for commuters and urban workers include significant productivity losses, soaring healthcare costs, and a decline in overall quality of life. We need to create compassionate and connected cities that belong to everyone.