11 Jan Risk-Taking in Duluth, Minnesota: Lessons Learned from “Imagine Canal Park”

Download the full Imagine Canal Report here.

Download the executive summary of the Imagine Canal Report here.

We spent a good chunk of our 2018 working with city staff and local partners in Duluth, Minnesota to test out new public space ideas. Sounds simple, right? Not quite.

In the case of Duluth, testing out new public space ideas meant making changes to an area of the city, Canal Park, that has not changed much in several decades. And real change is hard and rarely unanimous, whether it’s happening in a city of 10 million or 10,000. In the words of Derek Snyder, a Canal Park business owner, “If you don’t ruffle feathers, nothing is going to change”. And ruffle some feathers we did.

For those of you who are less familiar, Duluth is a city of roughly 86,000 people located on the western tip of Lake Superior. It’s the kind of place where there are a dozen craft breweries to choose from but also a 350-acre nature reserve located just 15 minutes outside the city center. On a short walk downtown, you’ll pass by an art house cinema, an outfitters store with all your hiking and hunting needs, and an old-school malt shoppe perched on the edge of a cliff. It’s a lovely place with a unique blend of urban and rural.

Canal Park is the city’s main entertainment district. 35 years ago, it was warehouses and scrapyards located on a narrow slip just south of downtown. Today, it attracts massive crowds of locals and tourists who come for the concentration of restaurants, shops, hotels, and opportunities to take waterfront strolls while watching giant industrial freight ships pass by.

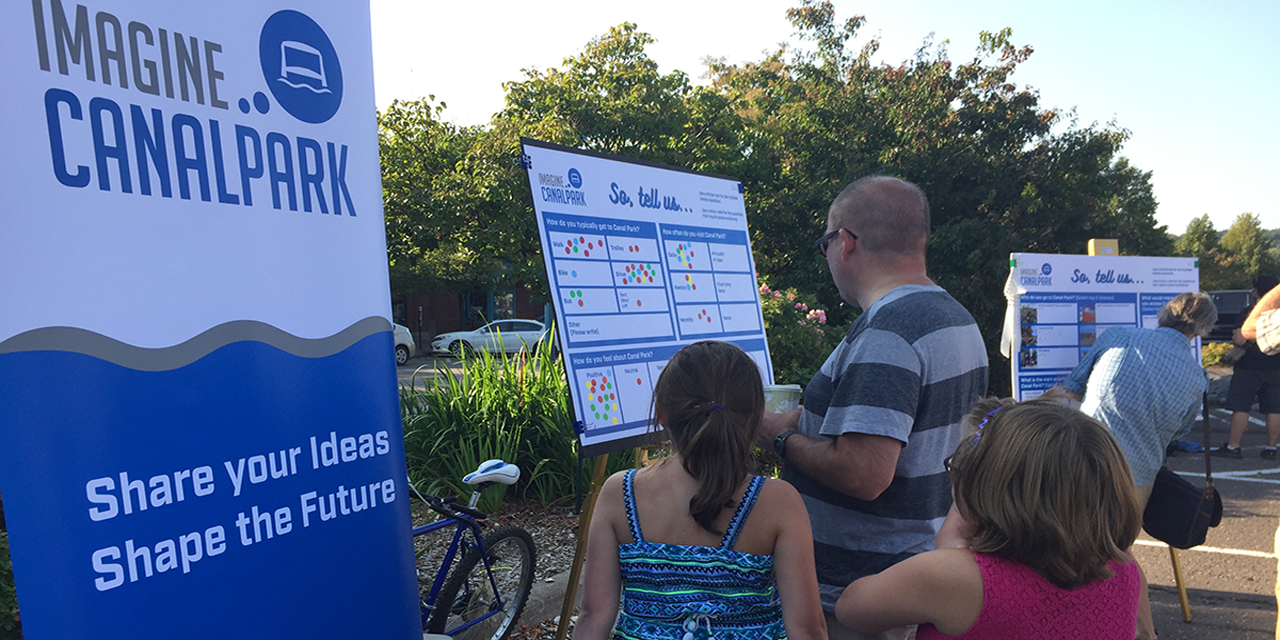

Instead of resting on their laurels, City of Duluth staff wanted to take another look at Canal Park to see how it could become even better. The City won a generous grant from Knight Foundation to kickstart a citywide conversation about the future of Canal Park and to pilot some of the ideas that came out of these conversations. What would make Canal Park fulfill its potential year-round? How can we create more space for people on this tiny slip of land? The City brought 8 80 Cities on board to find creative ways to engage residents and to evaluate the impact of these pilot projects.

After hearing from thousands of people, we landed on six pilot projects –an ambitious number to plan, execute, and evaluate in less than a year. Some of the pilots were more well-received than others. A free winter festival, well-designed wayfinding, and free trolley service? Who could argue with that?

The most controversial interventions were unsurprisingly the other three pilots that replaced space for cars with space for people. This included transforming a small road into a pedestrian plaza, converting a parking lot into a family-friendly recreational park, and reconfiguring vehicular lanes on a busy corridor to improve traffic flow.

These interventions provoked many strong, often angry reactions. Much of the negative feedback was rooted in feelings that traffic and congestion were already issues in Canal Park and that these interventions only served to make them worse. Does that mean that the projects failed? Absolutely not. You only fail when you don’t learn something from the experience. And we learned a lot of things! All of which we have captured in a detailed report.

But aside from the project-related lessons learned that in the report, I wanted to share four more process-related ones that are relevant to anyone who is embarking on a potentially controversial initiative:

- Stick to the vision, not the course of action: Even those who were opposed to how the pilot projects were executed expressed support for the concept underpinning them, which was to create more space for people. Moving forward, the City of Duluth remains dedicated to creating places for people but now has greater insight into what works well and not so well. They have a clearer direction now for how to tweak the interventions, whether in scope, design, or timing so that they are more likely to succeed in the long term.

- Communicate “the why”: We could have done a better job at telling the story of how we arrived at certain design decisions. Even though there was significant community engagement at the beginning and end of the project, we could have done more to involve the community throughout the entire planning process. This might have minimized some of the knee-jerk reactions that some folks had to some of the interventions.

- Find more opportunities to capture nuanced voices: Most of the online survey feedback was negative whereas most of the on-site, in-person feedback was overwhelmingly positive. For controversial projects, it’s hard to find those voices that are in the middle that could provide more constructive criticism of the pilots. Similar to my previous point, we could have included a variety of more touch points with the community throughout the project in order to capture these nuanced views.

- Aim for a culture shift: Imagine Canal Park was the first time the City of Duluth decided to experiment with their public spaces on such a large scale. Despite the controversy of the interventions, the public agreed that it was important to try to new things. This project gave Duluth residents a taste of what piloting is all about, while also providing city staff with the confidence to use the pilot project method to take more risks in the future. Creating this shift in culture and understanding among city staff and the public should be the cornerstone of any sort of controversial pilot project undertaking.

If you’d like to stay up to date on this project, please visit the official project website.